Legalities

The legal aspects of surveillance have come directly into the public eye in recent years, and is also a central theme in Cory Doctorow’s novel, “Little Brother”. In the novel, the US Government passes and suspends laws in order to increase their surveillance of US citizens after the terrorist attack in San Francisco. However, Marcus takes action against the government, organizing a group of his friends to secretly–and illegally–interfere with the government’s surveillance technology in an effort to protest the recently passed laws. Although what Marcus and his friends are doing is illegal, he justifies his actions by citing the Declaration of Independence,

“Governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.”

In our society, there have also been many recent controversies over what power the government should have in terms of surveillance and tracking individuals in our country. Many of the laws we follow today were written before the existence of digital communication, and there have been many controversies and landmark court cases over how current laws apply to these new forms of communication. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, the law works as such:

“Federal law includes all interstate calls, and there are several sources of authority for electronic surveillance in the U.S. The Wire and Electronic Communications Interception, and the Interception of Oral Communications Act typically require a court order issued by a judge who must decide that there is probable cause to believe that a crime has been, is being or is about to be committed. Wiretaps can also be ordered in suspected cases of terrorist bombings, hijackings and other violent activities and crimes. The government can wiretap in advance of a crime being perpetrated. Judges seldom deny government requests for wiretap orders.

Electronic surveillance involves the traditional laws on wiretapping–any interception of a telephone transmission by accessing the telephone signal itself–and eavesdropping–listening in on conversations without the consent of the parties. More recently, states have extended these laws to cover data communications as well as telephone surveillance. For example, in Florida, interception and disclosure of wire, oral, or electronic communications is prohibited. State and federal policymakers face the challenge of balancing security needs via electronic surveillance against individual privacy.” Source: NCSL.

This means that a phone can legally be wiretapped if a request is made to a judge and he approves it. This process was fairly straightforward when the most common method of communication was via telephone, however it is becoming increasingly complicated as modern technology evolves. In response, state governments have begun to expand the laws to cover the transmission of data, not just telephone calls.

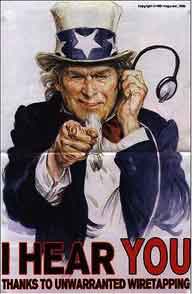

Poster protesting warrant-less wiretapping during the Bush administration

The NSA Warrantless surveillance controversy emerged after the President’s Surveillance Program allowed the National Security Agency to monitor any form of communication that originated outside the United States, even if the other party was in the country, without a warrant. The public responded negatively, and the program was discontinued in 2007.

The USA PATRIOT Act was enacted in 2001 by President George W. Bush, following the September 11th terrorist attacks. PATRIOT is an acronym that stands for Providing Appropriate Tools Required (to) Intercept (and) Obstruct Terrorism Act.

This act allows government agencies to gather “foreign intelligence information” from anyone, which ultimately blurred the line between criminal investigation and gathering foreign intelligence. If George Orwell were still alive, he might argue that emerging legislation from the United States has started to become unethical, and is moving towards the fictional dystopia portrayed in his novel, 1984. In “Little Brother”, the government passes an act called the PATRIOT Act II. This act gives the government power to monitor every time an American uses their credit or debit card, enabling them to see where you are, and where you have been. Marcus first learns about this law when a Turkish owner of a coffee shop informs him that he is only accepting cash, as a protest to the act. He views it as a violation of people’s freedom, and a violation of the Fourth Amendment.

The Fourth Amendment of The Constitution of the United States exists to protect the citizen’s “right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.” However, this amendment was written before the concept of electronic surveillance existed, making it harder to define exactly what types of searches and seizures the constitution protects. With the advent of the telephone, and later the Internet, it became much easier to track and monitor an individual even when they were operating in a “private” sphere.

The Supreme Court first considered the Fourth Amendment implications of electronic surveillance in olmstead v. united states, 277 U.S. 438, 48 S. Ct. 564, 72 L. Ed. 944 (1928). In Olmstead, federal agents intercepted incriminating conversations by tapping the telephone wires outside the defendant’s home without a warrant or his consent. In a 5 to 4 decision, the Court ruled that electronic eavesdropping involves neither a search nor a seizure, within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. The Court reasoned that no search took place in Olmstead because the government intercepted the conversations without entering the defendant’s home or office and thus without examining any “place.” No seizure occurred because the intercepted conversations were not the sort of tangible “things” the Court believed were protected by the Fourth Amendment. In a prescient dissent, Justice louis d. brandeis argued that nonconsensual, warrantless eavesdropping offends Fourth Amendment privacy interests without regard to manner or place of surveillance.

This sets a disturbing precedent, because with the rapid growth and development of communication technologies over the past two decades, it will soon be possible to conduct almost any manner of communication without ever leaving one’s house. Under the court’s ruling, this means that the government could legally listen to any and all of these communications because they technically never entered the house.