Bikram Patnaik

Visualization Link: Money buys Life

‘THE RICH LIVE LONGER EVERYWHERE, BUT FOR THE POOR GEOGRAPHY MATTERS’

Did it ever strike to you that the place our ancestors called their home could have been a matter of life or death for them? Today, everyone knows that rich people generally live longer than poor people because they can afford money to leverage hi-tech medical facilities, but what about people 2 Centuries ago?

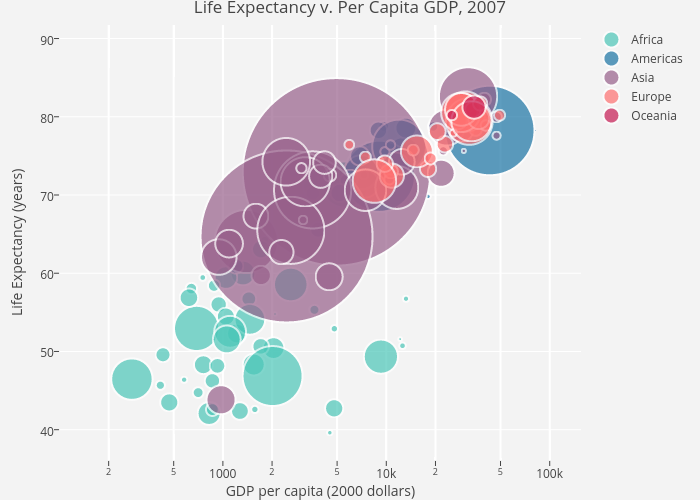

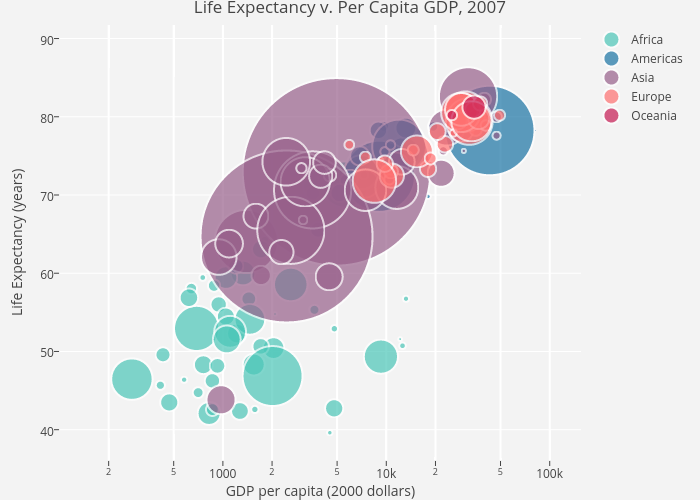

We will try to find answers to these questions and discuss if our main claim holds good by exploring this amazing interactive visualization.The visualization which we are about to discuss reviews data from 200 countries and compares life expectancy vs wealth for the past 200 years. The vertical axis shows the average life span in each country ranging from 25 – 85 years, where high up= long lives= good health, to the bottom= shorter life=sick. The horizontal axis shows the average income per person (GDP per capita) expressed in dollars per person per year, where the right=rich and to the left=poor. It’s interesting to see the usage of bubble chart for this, which is primarily used when you represent data that has three or more data series (In this case income, life span and size of the population) and each containing a set of values.

UNDERSTANDING THE DATA:

Let’s explore the visualization and understand it better. On the first look we can figure out that each country in the world is a bubble,the size of the bubbles represent the population size,color represents regions of the world (see on top right side). We start with circa 1800, all the countries had life expectancy less than 45 years and an income less than $4500. We can see that the United Kingdoms & Netherlands were among the richest countries but people in there had short lives. Underdeveloped healthcare systems and poor sanitation attributes to some of the reasons why all the countries had shorter life span and most importantly these acts as a warrant to our claim.

Now as we click ‘play’ the years start to roll in the world. Slowly income start to increase mainly in Europe and North America because of industrial revolution. As a result, they pulled away from the rest of the world. BUT, surprisingly health didn’t get much better. In 1900, only western countries were getting richer and richer and became healthier and healthier. Between World War I (1914) and WWII (1945) the difference between the rich and poor countries increase and it’s only after the WWII that most countries started to change in terms of wealth. The Arab countries became the richest and countries like China and India prosper as a result of their emerging economic growth.

Now in 2017, we observe a continuous world with high income countries (Qatar,Norway,USA) having a high life span and low income countries (Ethiopia, Niger, Liberia) have a lower life span, but interestingly all the countries are estimated to have more than 45 years of life expectancy, which only happens to be the maximum life of people in 1800. Though the difference between high income countries and low income countries are huge but their respective citizen’s longevity have come up significantly.

DRAWBACKS:

Undoubtedly the visualization is amazing in itself, but there are few snags which can alter the statistics if taken into consideration. First, the data collected are only with respect to inter-countries. But what it doesn’t include is the scope to look at the differences of incomes within the regions of a given country which would give insights to it’s growth/downfall. Second, while talking about population size of any country we only take into account it’s current citizens but there is a significant inflow of immigrants in these country every year contributing towards the economy. So there is a high probability that it might give us a different picture altogether.

FROM A CRITIQUE’S VIEWPOINT:

The number of different parameters presented on the interactive dashboard are overwhelming. For a new user it becomes hard and confusing, instead a simple drop down could be introduced to give the audience the flexibility to play around with their desired set of parameters. The vertical lines on the chart needs to be even spaced and the text for year should be at the top to avoid any kind of visual conflict. Also, while toggling on the ‘Map’ tab, it gives us an elliptical view of the globe and the bubble of each country doesn’t sync very well with their respective geographical location. This can be eliminated by displaying a flat world map view and being accurate about the geographical locations.

ALTERNATIVE APPROACH/MODIFICATION:

Though it’s visually appealing there are certain hiccups with this bubble charts visualization as well. It can be further enhanced and made simpler by adopting certain techniques.

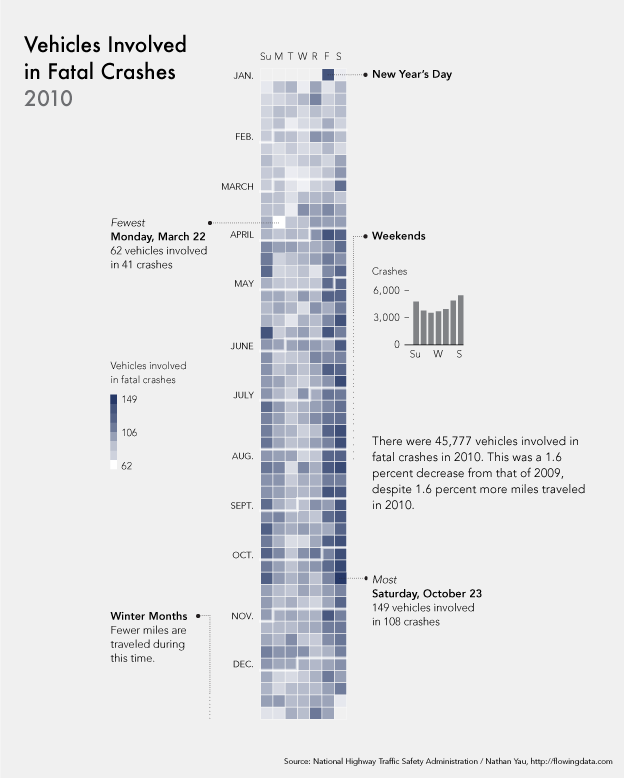

- The bubbles are opaque in nature creating a problem to clearly figure out countries with smaller population size. So, as an alternative I would recommend to use translucency and highlighting the boundaries of the bubble. These are powerful tools for dealing with over plotting, as you can see this in below visualization.

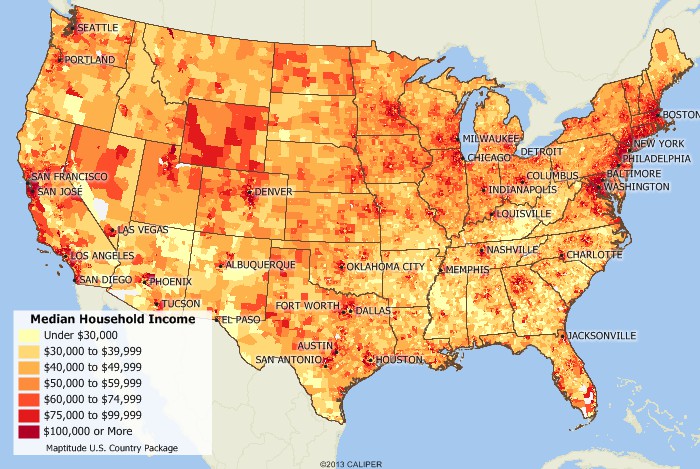

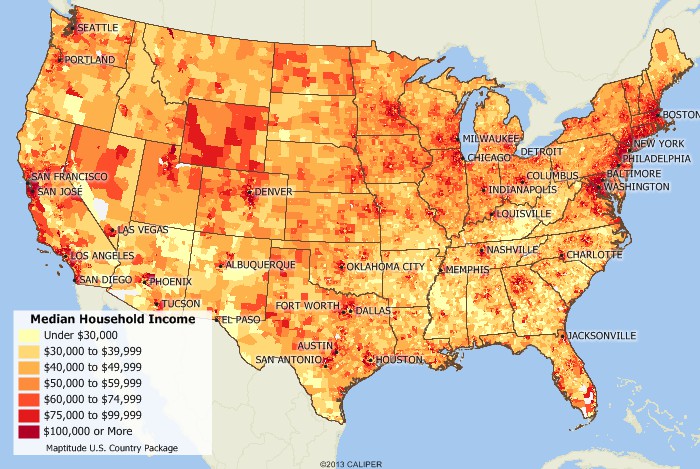

- As we discussed earlier that the visualization doesn’t show the differences within a country, It can be modified by introducing an additional feature in which by selecting a country say United States, it will give you an overview of all the data values for the 50 states along with an appropriate color contrast. The modified version looks like the below visualization.

CONCLUSION:

I feel that this kind of visualization is really helpful when conveying a large amount of numeric information quickly to your audience but at the same time ensuring that viewers are visually literate. An important part of bubble chart visualization is to make sure that it is clear what each element of the chart means – color, circumference, how it fits on the scale otherwise the whole meaning can be lost. Similar approach/viz can be an advantage for organizations to analyze their financial sales with respect to their customer base. It will help them to come up with business metrics and promotional plans for their consumers.

Reference: Harvard Gazette, The New York Times 1, The New York Times 2, MIT News

and Wallet Hub’s:

and Wallet Hub’s:  maps of state tax data.

maps of state tax data.